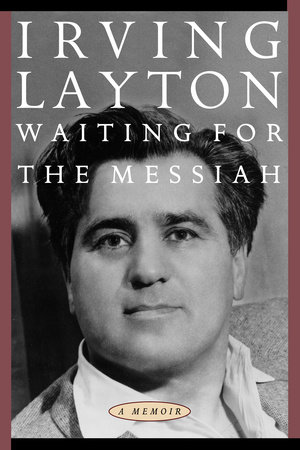

Waiting for the Messiah - a Memoir, Irving Layton with David O'Rourke

McClelland and Stewart, 25 Hollinger Road, Toronto

c. 1985. Hardback, 264 pages.

To this reader, it is hard to reconcile the initial chapter of this book

with the succeeding ones. Indeed, the further one delves in this

memoir the more it appears as though the reader has been made privy to

the maturing of a writer. The beginning chapters have a naivete, an

arrogance and even a kind of silliness (deliberately playful, let us

dare hope) which is off-putting and unworthy of the literary stature of

this man, despite his flamboyance and provocative style.

But, for those of you who may decide to embark upon this reading

adventure, a word of advice - persevere. It's worth it, for the work

steadily improves and becomes less tendentiously tedious (the initial

style and content going far to give credence that some people will do anything for attention and that advanced age is no guarantor of social or emotional maturity) and progressively interesting.

Less, alas, as a result of Layton's own life experience, more as a

fallout of his place in the times he writes of, and his relationships,

close, tenuous, distanced or what-have-you, with other, more

interesting, and sometimes more talented people than he.

Which is not to deny the man's estimable talent. I have tried to in the

past, mind, when his misanthropic and seemingly misogynist attitudes

have infuriated me to the point of denying the man his due - and my

adversary-in-opinion has been none other than my husband, an ardent

admirer of this latter-day bard - an unhappy experience.

Layton begins his memoir, logically enough, at the beginning. We are

informed that the incipient poet was 'born with the smell of baked

Challa in his nostrils', a startling revelation but infinitely less so

than his other well-known claim, that he was born with the messianic

sign - already circumcised. This affectation does not grow dim with the

passage of time, but since it offers a kind of comfort to the man there

is no point denying him that cushion.

During his growing, and omnivorously-reading years, he imbibed stories

of the lives of other saviours and heroes, including Moses, Buddha,

Alexander the Great - whose own births were accompanied by bizarre

circumstances, as his was. Thus was born a legend of self.

Once departing from that thesis, we are introduced to life in the

Lazarovitch family, with father Moishe, a soft-spoken, pious and

scholarly man who brought the shtetl

with him to Montreal; mother Klara who shrieks curses down upon young

Irving's hapless head; siblings Avrum, Dora, Esther, Gertie, Harry,

Hyman and Larry. And, of course, the extended family members, most

particularly the men whom sisters had wed, and whose foibles and

coarseness are discoursed upon at length. Layton's childhood was not a

happy one.

In a background of grinding poverty, in a family whose orientation was

mercenary (how else survive in the hostile environment for immigrant

Jews in turn-of-the-century Montreal?), the emerging intellectualism of

the young boy with a mischievous temperament was a puzzle and a nuisance

to his family. While Layton was increasingly drawn by education, with

an emphasis on literature and the beauty of language, his increasingly

alienated family demanded that he assume the life of an itinerant

peddler, an occupation at which, fleetingly, given his gregarious

character, he was able to succeed very well at.

But Layton had a self-vision of a glory greater than earning dollars

with which to support himself, and eventually evolve into budding

mercantilism. His love of, and admiration for poetry, was first

inspired by the beautifully rendered readings of Tennyson's Ballad of the Revenge by one of the few teachers for whom Layton had some modicum of respect at Baron Byng High School.

In total, Layton's experiences with teachers in general throughout the

public school system, and on into college were dismal, demoralizing

affairs for the budding scholar/poet. Insensitive clods they were,

demineralized, myopic, harsh, coldly demanding and censorious of the

high-spiritedness of a rebellious adolescent with a penchant for

learning, but only in the environment of nurturance, which was, alas, a

scarce commodity.

He had a budding romance, both with a young woman (and by extension, her

mother) and with the dialectic of communism. With the former because

he was a normal, lustily yearning young male, the latter because it was

socially verboten. After that flirtation, Layton dabbled, with friends

who drew him into their circle, with socialist ideals. He met, and

became a personal friend of David Lewis whose analytical and brilliant

mind he appreciated, but whose oratory he felt was far from brilliant.

Through Lewis he met Abraham Klein, then a young articling lawyer, and

language-precise, fiery poet with whose help he was able to master

Latin, and make his senior grades.

A chance encounter led him to attend college, at a time when Layton was

drifting along, with nothing much else to do but earn the odd dollar to

keep a roof over his head and go to meetings at the Young Peoples'

Socialist League communist meetings, and Horn's Cafeteria, the hangout

for social radicals of the time where social responsibility,

proletarians' rights, Marx and Engels, the Communist Manifesto, the

evils of the capitalist class, unions and labour were discussed with

resounding vigour, and the pilpul of opinion had its day.

In that forum Layton was exposed to the explosive mixture of socialist

and communist thought, Trotskyism, anarchism. It was a heady, pleasing

ongoing experience for the young man, which he balanced with his private

readings of Shelley and Keats, trying to hone his own, by then, not

inconsiderable skills, both as an orator, and a poet. Very little of

the social cant, of the traditional exposition to which he was exposed

was taken at face value; he observed and trod daintily among the ideals

and ideas, although his admiration for some of the exponents knew no

bounds.

This was the Quebec of the Catholic Church with its stranglehold on the

thoughts and minds of Quebecois; it was the Quebec of Arcand, and of

police brutality. And this was a Layton whose mind and heart were torn

between social activism and literary endeavour. In the end, his

literary ambitions emerged victorious, although there is an inescapable

thread of social activism in the warp and woof of his literary work.

The college of Layton's choice turned out to be Macdonald College,

chosen for the logical reason that it was the only institute of higher

learning which he could manage to afford. Associated with McGill

University, the only degree this college conferred was that of

Agriculture and this explains neatly why Layton's degree is in this

area.

Because of the cautious, conservative, intellectually stilted atmosphere

of the college, Layton decided that he would form a speakers' club

which he called the Social Research Club. To its regular meetings he

invited the then-president of the Royal Bank of Canada, followed in

fairly rapid succession by the pacifist Lavell Smith, the fabled Dr.

Normal Bethune, and the founder of the CCF, J.S. Woodsworth. His plans

to also invite Tim Buck were thwarted by the organized efforts of other

members of the student body who feared the college would be irremediably

tainted red, thus scuttling their future plans for a civil service

career.

Layton experienced a great deal of satisfaction in knowing that exposure

to these fiery speakers of the time, some of them exceedingly

controversial, opened up the minds of their student listeners. Even so,

the reputation that Layton acquired while at the college was not that

of a social facilitator, but that of a rabble rouser, and both the

unlikely appellations of 'Hitler' and 'Trotsky' often crowned his

reputation there.

Layton mourned the sad fact that while at college the literary-poetic

idols held to review and admiration were those of the era of Edwardian

England, and as delightful and earth-shaking at their time as they were,

they did not reflect the social and cultural tradition of the country

and the times which he inhabited. He professes to some bitterness at

not having been exposed to the works of T.S. Eliot, Hart Crane, and Walt

Whitman, let alone Canadian poets like Lampman, Bliss Carman or E.J.

Pratt.

This lack left him with the impression for too long, he felt, that he

could do no better than to emulate their style. It was when he became

exposed through his own search and pique to the work of these

ground-breakers that it dawned upon him what progressive poetry, free

verse reflecting the temper of the times could really accomplish.

The man, obsessed with the earthiness of life, of passions unleashed,

scorning convention and the limpid and sexually repressed poetic style

of his peers, evolved a poetic address uniquely his own. One that

shocked both the reading public and the then-literary establishment. It

was not 'polite'.

He writes of his marriages, of his attachment to women, to his ideas and

his poetry. He writes of the joy and ecstasy of creative achievement,

of self-affirmation in the final realization that one is yes indeed, a

poet of incalculable creative ability. Which there is no denying Irving

Layton is.

This is a good book, a rewarding book, and in its own way, a revelation,

Messiah complex aside. For in his very own, inimitable way, Layton

really has been a messiah; he has helped to unleash unbridled sensualism

in poetic expression, given it a fire of his own devising, and brought

poetry where it belongs, in the gut as well as the mind of the reader.

Abrasive and even abusive he can be at times, but where is there a poet

whose totality is perfection? It is unfortunate that Layton's very

well-publicized divergence of opinion with Elspeth Cameron and his

dismissal of her 'unauthorized' biography of him did not result in an

increased public interest in his own book. One has the impression that

the increased notoriety he might have traded upon as a result of the

acrimonious exchanges in the media would translate itself in brisk

sales, but alas, volume one of his memoirs has not sold well.

Still, he's preparing to write the second volume of Waiting for the Messiah and this reviewer, however inclined to be critical as I am, intends to wait for that messiah. Stay tuned.

No comments:

Post a Comment