|

His

English teacher, the final year of high school, encouraged him to

write poetry, "Learn to express yourself. You'll find it's a good

outlet for your emotions. Poetry is the only completely honest medium",

Mr. Stevenson said.

Michael read Eliot, Pound, Frost and Wilde

but he felt dissatisfied. Accidentally, he discovered the biography of

Sir Richard Burton, felt a current of recognition, and went on to read

Burton's translation of Sheikh Nefzawi's "The Perfumed Garden". His

head reeled. And he unburdened himself.

In the school library, writing. The poem held everything he dreamed of, and it was honest. His name scribbled on the top.

Was

it accidental that he left it there or had he forgotten? Did he really

think someone might come across it, be struck by its tender pathos, the

passion, the genius of it?

The school office was nicely appointed; the only part of the building that didn't resemble a jail, a barracks.

"We won't tolerate this kind of ... obscenity!" Mr. Pearce spat out the distasteful word, jowls trembling in outrage.

Michael

almost panicked. They threatened to throw him out of school. It was

two months before final exams. He was humble, explained it to Mr.

Pearce as a temporary lapse. He was not himself. He didn't really

think that way - maybe it was something he'd read somewhere. And no, it

wasn't true that he'd written it for Gayle Pointer. He didn't know

who'd picked it up, given it to her.

"You're on borrowed time, Brack, remember that! Henceforth, your behaviour will be the model of circumspection."

"Yes sir."

***********************************************************

His

father looking at him with that grim expression. Michael forced

himself to pick up his fork, lift a piece of potato, open his mouth to

receive it, chew.

"I'm talking to you!"

"Yes sir, I can hear you."

"Where did you pick up that kind of thing - not here! Not from us!"

"No sir."

His

father, shoving back his chair, rising. "I won't sit here with him ...

none of us have to, Rachel! From now on see he eats before we do."

Michael

rummaged about in the accumulated debris of the night table in his

parents' room until he found what he was looking for, knew they were

there. He punctured them, every one, then carefully rolled them. They

looked innocent, untouched.

**************************************************************

"I'm

sorry Mrs. Brack", the doctor had said when he was a year old, in the

grip of a prolonged high fever. "Even if he pulls out of this you can't

expect him to live long."

Later it was, "Even so, he'll be a

vegetable. He'll never be able to communicate, to talk. I've heard of

other cases like this one. He'll be a vegetable for however long he

survives."

It was relatively easy to abort a foetus, withhold

medical support from a newborn. Harder to do anything about low

expectations for an infant. He was already an established fact, an

entity to deal with.

He walked, he talked. Animated, like a hopeful robot, waiting for some response.

"Jesus Rachel! Can't he even act like a normal kid? What's he keep staring at me for, with those goggle eyes?"

*******************************************************

When

he was nine, he had an Abyssinian Guinea Pig, kept it in a cardboard

box with rumpled newspapers. Freddie. It dug into, under the

newspapers, made itself a private little cave. The animal knew him,

recognized his step, his voice, squeaked for attention when it heard

him.

Michael fed it lettuce and apples. The animal dogged his

footsteps, a bundle of brindle fur. Soft and warm, he let it snuggle

under his shirt, next to his skin. It loved him, liked him for being

warm, for caring for it.

Once, his hands stopped in their

caressing motions over its back. Stopped and went back to check, again

and again. The hump grew day by day and then there were other, smaller

humps.

Freddie wound down, his squeals were faint and instead of following Michael, he sat there, squatted on the floor, still.

Michael

buried it in the backyard, under his mother's rosebed. The roses grew

bigger and brighter than ever that year. He hated the smell of them.

They smelled corrupt.

************************************************************

At

the university cafeteria, him sitting alone at a table for four.

Seeing someone whom he recognized from one of his language classes come

in. Michael rose, waved for attention, indicated the empty chairs

beside him.

The searching face stopped, glanced at him, an annoyed expression fleeting across the face, then continued its search.

It

wasn't just him, that he'd contaminate anyone. It was just society.

Space was precious. No one wanted anyone else to intrude on their

privacy. No one looked for unwanted intimacy, even the superficial kind

his invitation represented.

It wasn't just him.

*********************************************************

Factory

smoke hanging thick and pungent over Cornwall. Himself wandering along

the bank of the St.Lawrence, watching ships pass. Seagulls swooping,

riding the crest of the wind, shrilling.

There were Greek

immigrants there, industrial workers. In his grade five class, one who

took him home. A big warm family who saw nothing different about

Michael. They fed him lamb and rice parcels rolled into grape leaves,

taught him Greek words.

The shawled grandmother, brooding and

immobile, dreaming of a lost blue sky, the balmy Aegean, olive trees as

gnarled as she was, but productive in their venerability.

Michael

discovered a facility for languages. And when he spoke the foreign

words, remembering them from visit to visit, expanding a lean

vocabulary, his tongue no longer faltered and tripped, extending the

words impossibly.

*****************************************************

The

first individualist who insisted on worshipping Aten when everyone else

was dedicated to Amon-ra and the lesser gods. The narrow, aquiline

face. Narrow shoulders and pendulous belly. But refusing to be

idealized. No shapely waist and wide shoulders to depict him. Nothing

but the reality would do.

Michael felt an affinity to the antique

figure, a recognition of self. The face, proud and noble. No one

could tell that that face, his frailty, his misshapen figure was not

beautiful.

Of course, after his death, the jealous priests

exhorted restless hordes to erase all evidence of his greatness, to

chisel his name out of posterity.

The Brotherhood of Man is the

safety of the masses, the sameness of physiognomy and predictable

aspiration. There have been, and are, a handful of others and they

suffer, Michael consoled himself.

*******************************************************

Studying

at the university library late at night. The place almost deserted,

huge and hollow sounding. He could hear his breathing almost, his heart

beating like strange music filling the empty spaces of the chamber,

bouncing off the books.

Michael let his mouth fondle the

Chaucerian Middle-English, felt his fluid tongue quiver with the beauty

of the sounds playing in his head.

The sound of something

rasping. Over at the card catalogue, a lone figure pulling out a

drawer, lifting it out, taking it over to a table, laying it down and

bending over to riffle through the cards. A woman, small and dark, her

backside rounded, pointing at him.

A warm flush suffused him and he felt himself, tumescent.

What

would happen? If he silently approached, placed his hands on her hips

and drew her toward him. He could feel her against him, the softness

and warmth of her. He could lay his face against her hair and the

freshly washed fragrance of it would cradle him ... but she turns

around, angry and frightened, lifts her hand, palm open, to slap him.

Calls him 'creep!'

He retreats, stumbling in his confusion, apologizing, his voice tripping over the words, agonizing.

But

she's gone, doesn't hear his explanations. She's gone to the other end

of the library and he watches, frozen, as she talks excitedly to a

security guard. Sees as the guard turns to stare at the end of her

wildly pointing finger, Michael standing there, exposed.

It

hasn't happened, none of it. Michael is still sitting at the library

table, still tracing the words with trembling finger on the book, and

the girl has found what she was looking for, shoves the file drawer back

in the cabinet. Her heels click businesslike and impatient on the

floor, echoing through the silent chamber as she walks off.

******************************************************

"I'm the first one in my family to break away from the duenna-mold. I'm the oldest. It'll be easier for my sisters."

"But there's something nice about that, too. It means they care about you, doesn't it?"

"Yes,

they do. But you've got to understand, it's all done to protect the

girl's reputation. If they suspect she's done something wrong, she

isn't worth anything on the marriage market."

"Oh."

He

likes her, her casual acceptance of him. Her fragile height, and her

black cap of hair. Her defiance of old-world custom while still

maintaining about herself an old-fashioned rectitude. Ramona.

"Tell me something else, Michael - it's fascinating."

"Okay well ... marmalade! Know where that comes from?"

"No."

"When

Elizabeth had Mary in the Tower, one of the warders felt sorry for

Mary. He cooked up some slivered oranges and sugar and took them to

her, saying 'for poor Mary-my-Lady'".

Michael reads to Ramona

from his original Beowulfian text, his voice a Teutonic sing-song,

masculine and controlled. the Old English mellifluous and soaring. He

feels himself transported, exhilarated, as much by the perfection of his

sly transpositions - Essex to Kent to the more common Wessex dialect -

as by the rapt expression of respect on her face.

Next time, he

promises, he'll render the original texts of Averroes, Avicenna and

Halevi. She hangs on his words, sees him as he is meant to be seen, as

he sees himself.

Of course she can't understand what the rare

words mean, but she understands well enough what they are meant to

convey. They are a consecration, a sacrament. Michael's love song to

her.

At a Byward Market store, he found a shawm. Oh, not the

real thing, but a folk instrument, made in mainland China. Only a few

dollars, and he was delighted to have it. Taught himself, slowly and

painstakingly, the fingering. Learned to soak the reed beforehand, and

to blow up his cheeks to force wind through the narrow aperture.

The

sound was harsh, demanding, like a wounded bird. It was perfect. He

could play medieval music on it. He could read his Middle English and

then play the appropriate music; recreate for himself a more admirable

time in history.

He haunted the Medieval and Renaissance sections

of Treble Clef, waiting for any new materials that came in. He learned

the musical conventions of the time both by reading its literature and

by listening to the recordings of early music groups.

He'd try, when he saw someone else looking for such esoteric music, to break ice.

"Let me know, will you, if you come across something by Musica Antiqua of Amsterdam?"

"I'm looking for the Academy of Ancient Music of London, myself."

"Play anything?"

"Yes, rauschpfiffe and recorder. You?'

"Ah ... shawm, and I'm looking for a krumhorn."

"Hey, great! You play with anyone?"

But

he'd always spoil things, somehow. His enthusiasm, perhaps, and the

accompanying physical signs. His bobbing head that withdrew into his

neck sitting on his hunched shoulders; the twitching left eye, made him

resemble a nervous turtle. If they were too well-bred to laugh

outright, they'd walk away coldly.

In his desperation to redeem

himself, he'd spout gratuitous information after them. That the

sackbutt was the forerunner of the trombone, and the curtal was the

forerunner of the bassoon, the shawm that of the rauschpfiffe. No one

really cared. No one came back, impressed.

****************************************************

"Michael, everyone has headaches!"

"Not like this, mother, surely not like this? I didn't always have them."

"There's always something the matter with you! If it isn't your back, your feet, your eyes, it's something else!"

"I can't help it, it's not my fault."

"Not

my fault either, but it's time you learned to put up with your ...

uneven health. And for god's sake, don't complain when your father's

around, you know how mad he gets."

At last the headaches went.

After suffering them eight long years and no one believing him. The

Ottawa ophthalmologist discovered what was wrong, told him that what the

other eye doctors had been doing was treating each eye individually,

forgetting that they had to mesh for clear vision and the new lenses

would correct the right eye that always seemed to be looking straight

down at the ground.

With the new lenses, he had to learn

distances and perspective all over again. Peoples' noses now leaped out

at him, the ground was further away than it had always been. The result

was that he seemed more awkward than ever during the period of

adjustment. It was like discovering a new dimension and he thought he

knew how the 14th-Century Florentine artists must have been stimulated,

delighted and frustrated by their attempts to come to grips with the new

reality.

Temporarily, he became again a figure of mild ridicule as he stumbled, learning to re-align images.

****************************************************

Mr.

Seguin has worked for the Merchant Marine Branch of the Records

Division of Transport Canada in Ottawa for thirty years. He's an ugly,

fat little man, with an engaging manner, and he knows how to handle

people. Mr. Seguin has recognized in Michael someone with whom he can

discuss opera.

Every holiday Mr. Seguin and his son go to Rome or

New York for the opera season and Mr. Seguin goes backstage to

personally greet, like old friends, international opera stars with whom

he has become acquainted over the years.

"Don't tell me, let me guess", Mr. Seguin says, sniffing the air, eyes shut, "that's a Cape Breton ... not a Lunenburg odour."

How

does he do it? He's usually right, although one fish smell seems the

same as another to Michael. The men step off the elevator, clothes

reeking of their livelihood, to renew their merchant-marine licenses.

They're sometimes pugnacious, shy, or resentful, and Mr. Seguin jokes

with them, putting them at their ease in the cold atmosphere of the

government office.

"You're doing fine, just fine Michael", Mr. Seguin encourages him. "There's a CR-3 in your future."

Michael nods his appreciation, doesn't tell Mr. Seguin that it isn't this kind of security he's looking for, but his Aten.

**********************************************************

The Maggiores are a big family, close-knit and volatile, Ramona tells him, warning him.

When

Michael comes by to share their Christmas dinner by invitation, he's

introduced and later can't remember - Vittorio, Vincente, Aldo, Mario,

Anna, Rosa, Clarissa, Maria - which names belong to which faces. Ramona

smiles empathy.

They're voluble and excitable, a throng of

flailing arms and legs - rising voices - rushing over to hug each

newcomer. And they're also sympatico and courtly in a now-forgotten

way.

Dinner is seven courses of fish. Dinner takes four hours as

each dish is savoured, wine is had with each, then a half-hour

interval, while everyone talks, and the next course is served.

Michael

ate the eel boiled in the eelskin, thought it was bland. And one other

fish, whatever it was, a herring of some sort, that he couldn't eat for

the bones. All the other courses were a blur of tastes and

exhortations - "take - take!"

After, when everyone rose from the table, he made his way to the opposite end, where Ramona sat with all the other women.

"No", she whispered urgently, colouring. "You've got to stay with the men."

He experienced some difficulty following the Sicilian dialect. They spoke so rapidly - of soccer, cars and politics.

*******************************************************

"Isn't it hard?" Ramona asks him, "working all week and then coming out to evening classes?"

"Need is the mother of necessity", he quips, feeling strangely naked.

"I mean, what's the point if you've got a job anyway?"

"I've got a goal."

"What?"

"I want to teach speech therapy."

"Why? Why that?"

"Because ... because they said I'd never speak. Because everyone laughed at me when I stuttered and fumbled my speech."

"Michael ... you don't, anymore!"

"No,

I don't. And it's because ..." He broke into a melange of tongues.

Meaningless to her, the kaleidoscope of languages. She could see that

he was teasing her, speaking musically, lightly, humorously.

"I've

almost got my B.A. I need my M.A. and then I'm set", he tells her.

She nods. She has an immense respect for his determination. His

facility impresses her.

********************************************************

Michael's

had two wisdom teeth surgically removed. They were impacted. Although

they hadn't bothered him yet, his dentist said they should come out

before they caused serious trouble.

He's in his new quarters.

The room's larger than his old one, the bathroom not as far down the

hall. Nice, except that the refrigerator doesn't work properly and

isn't big enough to accommodate everyone on the floor.

He's sorry

he left his old place with such bad feelings on both sides. But he

hadn't made as much noise with his music as they said he had. Not

nearly as much as the kids playing their damn rock.

His closest

neighbour, the man next door, is from Nigeria, black as the Queen of

Sheba. His name is Abo, and he grins whenever he sees Michael, and

ducks his head from that great height, in acknowledgment.

Abo is

always carrying books and keeps his portion of the refrigerator stocked

with exotic-looking foods. Since the fridge doesn't work well, they

quickly go bad and stink up all the other food, but Michael doesn't want

to say anything. He likes the white-on-black greetings.

Once,

Michael saw Abo hurrying along Market Street holding a live fowl under

his arm, and wondered what the black man was intending to do with it.

Now, he feels feverish, and turns in his bed, annoyed that he doesn't feel like studying. She'd said ....

*********************************************************

"I

told them I'd be studying late at the university, she says, bringing

the fragrance of an afternoon snowstorm with her, lightening his room.

"How do you feel?"

"Dreadful", he groans.

"Poor boy."

"Absolutely awful."

"Oh, Michael!"

How could she like him? Want to be with him? She's touchy about her height, thinks she's a dwarf, but she's perfect.

"Ramona ..."

"Michael?"

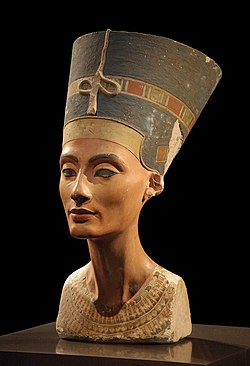

"Ramona, have you ever heard of Nefertiti?"

"The Egyptian queen?"

"Yes."

"That's

all I know, that she was an Egyptian queen", she says, sliding out of

her skirt, her slip, raising her sweater over her head.